FEATURE

What’s in a Name?

How Words Are Monuments

SHARE

Place names are never neutral—they shape how we understand and inhabit land. Naming is both a tool of colonial power and a site of insurgent resistance. What stories do official names establish or erase, and how can naming be reclaimed to reflect cultural survival, justice, and collective care?

Officially called toponyms, place-names are the names attributed to geographical areas at every scale—from the street to the continent. These names are registered with regional, national and international boards of geographic names, formal organizations dedicated to the standardization and registration of official place-names. We encounter place-names all the time, relying on them every time we pull up an address on Google Maps, and every time we send or receive a package. Place-names are also a key part of the shared language through which we come to understand and navigate the world. Place-names comprise one layer of the immaterial map that is laid overtop of the material world, conjoining with other topographic descriptors to orient people to place. They shape consciousness, recruiting us, in everyday life, into a manner of seeing, understanding, and relating to the land.

What does it mean to say “Words are Monuments”?

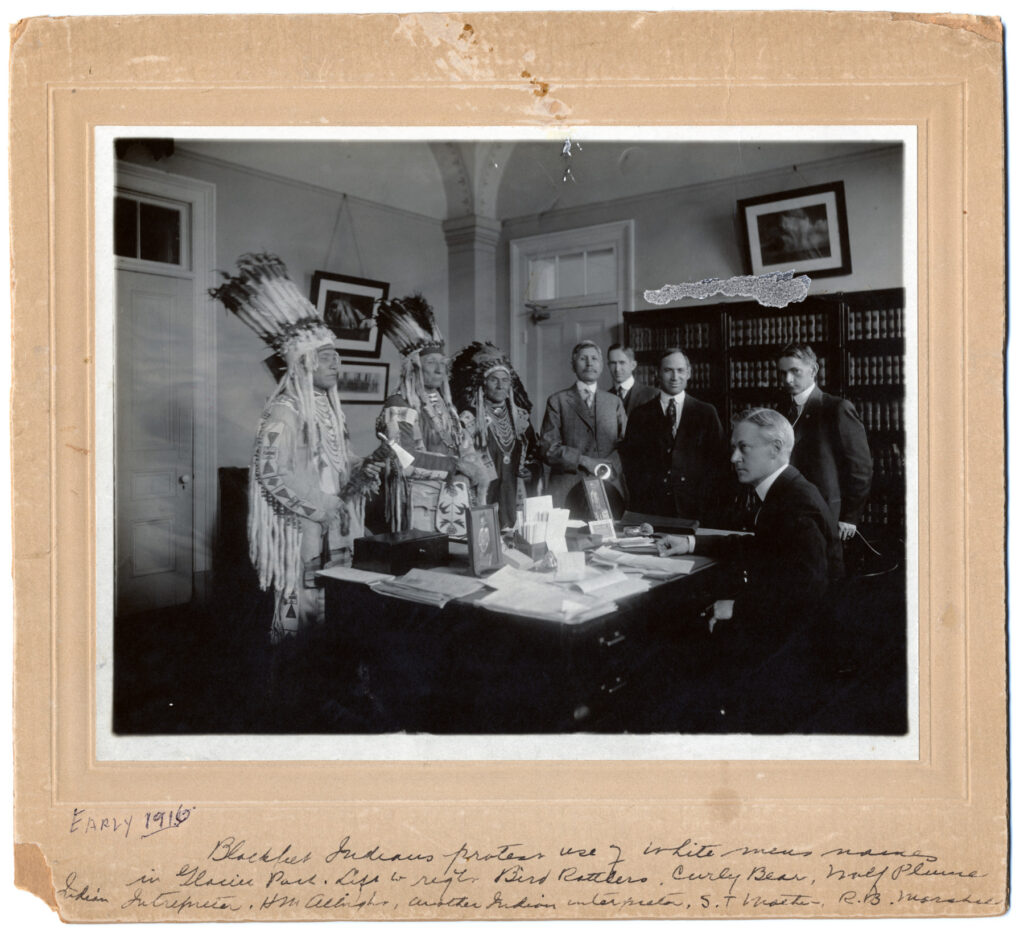

Place-names existed long before federal registries and geographic naming boards. In the United States, vast swaths of the country were occupied by Indigenous Nations for millenia, which had their own linguistic traditions and naming practices before the first Europeans arrived. As colonial and commercial expeditions traveled westward across the continent, villages, forests, rivers, mountains, and other geographic features, many of which had long-standing Indigenous names, were given new names. Some were named after the tribes that stewarded the land; others were named after European towns and cities where the first settlers were coming from. “It was only natural,” one researcher explained in 1925, “that the European colonists who first settled on the shores of America should commemorate their sovereigns and patrons by naming places in their honor.” What came “naturally” to the European colonists was domination. For them, naming was equivalent to claiming.

From the colonial perspective, place-naming is an exercise in power and authority, a symbolic means of claiming sovereignty over a place. It is also a cartographic exercise—one part of a project of mapping the world, which, in settler colonies like the United States, was a means of rendering the Indigenous world intelligible, and therefore manageable by the federal government and its armed forces. For people whose ancestors were dispossessed of their tribal homelands and subject to brutal practices of cultural genocide (including the banning of Indigenous languages and cultural practices), colonial place-names are an extension of a long and ongoing project of forced assimilation—a violent means of forcing Indigenous Peoples to navigate the world according to coordinates defined by their colonizers. Like monuments to slave traders and genocidal colonists, colonial place-names are a source of ongoing violence for the descendants of slaves and colonized peoples who are forced to encounter them on a daily basis. As “spatial acts of oppression,” monuments work to set the historical coordinates through which people encounter the world.

Toppling Word-Monuments

Faced with this long history of erasure and dispossession, it is no wonder that Indigenous communities across the country are campaigning to have colonial place-names replaced with their Indigenous names. The goal of such renaming campaigns is not simply to make the settler-colonial world less offensive—to change place-names without changing the material conditions that they enshrine. Rather, their goal is, much more expansively, to nominate place-names as sites in a multi-pronged struggle against the ongoing dispossession of Indigenous peoples and their lifeways. These renaming campaigns are part of, and not in competition with, other land-based struggles for Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination.

The Indigenous-led renaming campaigns taking shape across the country serve to unsettle long-naturalized settler-colonial claims on the land. They are part of a broader struggle to break from the system of relations that colonial place-names reinforce. As renaming campaigns struggle to undo the colonial map, they point toward another map of the world—a world in common, beyond and beneath the colonial enclosures. Like the resurgent efforts to topple and replace colonial and confederate statues, renaming campaigns activate the settler-colonial world as a terrain of struggle, demonstrating how oppressive monuments, including word-monuments, can be replaced and reclaimed as life-affirming sites for cultural resurgence and decolonial power-building.