In January 2023, the federal government announced that it has concluded an historic yearlong process of renaming more than 660 geographical features whose names contained the derogatory slur “sq**w.” The term has been wielded as a racist and misogynistic epithet against Indigenous women since at least the 17th century.

Many of the new site names are in fact very old names, selected by Tribal Nations with ancestral ties to the land and traditional names for those places. Some of the replacement names were borrowed from nearby geographical features, such as the newly named “Isabella Creek” in Michigan, named after the lake it flows into. Other sites, like Lynn Creek, Texas, were renamed to honor people who once lived there.

Naming Problems

This accelerated renaming process was overseen by the Derogatory Geographic Names Task Force established by the US Department of the Interior (DOI), and involved a public comment period that yielded 6,600 comments and more than 1,000 proposed names, as well as government to government consultation with Tribal Nations, which yielded another 300 recommendations. As you can imagine, the process was anything but straightforward. The DOI explains:

“The renaming effort included several complexities: evaluation of multiple public or Tribal recommendations for the same feature; features that cross Tribal, federal and state jurisdictions; inconsistent spelling of certain Native language names; and reconciling diverse opinions from various proponents.”

For the DOI’s initial list of suggested replacement names, released last year, the agency “conducted a survey of place names near the locations in question, offering them as default replacements.” This process had the consequence of generating names with mostly colonial origins. As Sara Palmer, chair of the Washington State Committee on Geographic Names said, “You pick the five closest names around any given geographic feature and you end up with White, Bonneville, Columbia and Franklin Delano Roosevelt.” Washington’s Committee on Geographic Names took immediate action, appealing to the region’s Tribal Nations for proposals that could serve to “honor Indigenous women and their histories.” Elsewhere, offensive place names were swapped out with names that, while less derogatory on the surface, ultimately serve to re-enshrine settler-colonial relations to the land.

Commemorating Displacement and Dispossession

Take North Dakota’s “Sq**w Gap,” a hamlet in western North Dakota, which has been newly consecrated as “Homesteader’s Gap.” As reported by the Associated Press, there was significant resistance to changing the name at all.

“McKenzie County Commission Vice Chair Kathy Skarda grew up in the Sq**w Gap area just west of Theodore Roosevelt National Park’s North Unit. She said her friends and family thought the renaming effort was a joke. She also said she doesn’t think the name was ever meant to deride any ethnicity. People will have to live with the name change, she said, but the area will always be Sq**w Gap to residents.”

Through the public comment process, local residents reluctantly proposed Homesteader’s Gap, “citing the area’s homestead heritage.”

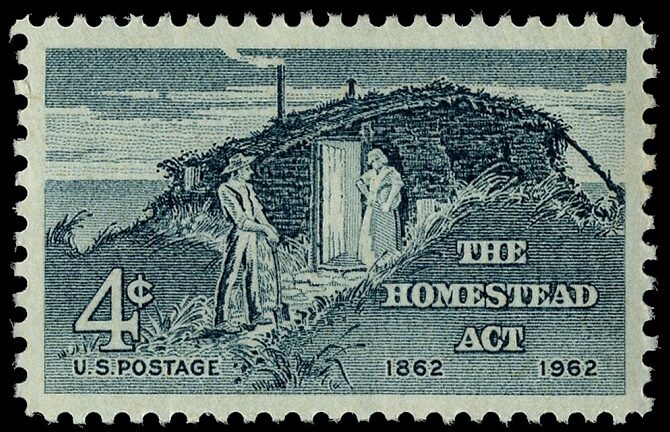

The hamlet’s new name commemorates the history of homesteading in the western US, a project that was supercharged following the passage of the Homestead Act of 1862, a federal policy that aimed to “accelerate the settlement of the western territory by granting adult heads of families 160 acres of surveyed public land for a minimal filing fee and five years of continuous residence on that land.”

Some historians have argued that the Homestead Act was not a driving force behind the dispossession of Indigenous lands, since much of the prospecting for mining, farming, and other settler industries had already taken place before 1862. This was not the case in what is now known as North Dakota, the traditional homelands of the Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Sioux, and Chippewa tribes. There, the Homestead Act expedited the deliberate process of primitive accumulation, where collectively stewarded lands were converted into private property, to be owned and cultivated by individual settlers.

By enclosing the land in this way, the United States government imposed a new settler-colonial logic on the land. In the process, the land base of Indigenous Nations dwindled by 99%, and everything else was submitted to the logic of capitalist exchange.

paper; ink (slate); adhesive / engraving, National Postal Museum

Homesteading was not only a form of legalized land theft; it was also an expression of what legal theorist Brenna Bhandar calls a “racial regime of ownership,” an ideological framework that “render[ed] indigenous and colonized populations as outside history, lacking the requisite cultural practices, habits of thought, and economic organization to be considered as sovereign, rational economic subjects.”

This regime of ownership did not only serve to demonize and delegitimize the cultural lifeways of Indigenous Nations. It also devastated the land and its other-than-human inhabitants. As the National Parks Service explains, after the passing of the Homestead Act, “the buffalo numbers decreased, domesticated animals increased, fences were built, water was redirected, more non-native crops were planted, unsustainable farming methods increased, native plants diversity dwindled.”

We live in the world that the Homestead Act helped to make.

Two Ideas of Land

Under settler-colonialism, land is understood as a commodity like any other—a scarce resource that can be “speculated, bought, sold, mortgaged, claimed by one state, surrendered or counter-claimed by another,” as Secwepemc activist George Manuel aptly explained in 1974. By contrast, for Indigenous communities, Manuel observed, the land is regarded as the sacred source of all life, and can therefore not be privately owned or exploited for profit.

Settler-colonial place names like Homesteader’s Gap orient us within the world that settler-colonialism built, making it difficult for us to imagine, let alone see, relate to, and organize around, the world it was built to eliminate.

What if we understood the movement to rename places not as a movement to make the settler-colonial world less offensive, but to affirm the enduring presence of the world that settler-colonial place-names have historically served to obscure?

Beyond Offense

There is nothing overtly offensive about the name “Homesteader’s Gap.” It has no racist or misogynistic connotation. And the residents of Homesteader’s Gap are correct: the new name does reflect the history of the place. The problem is that even when they do not overtly denigrate marginalized groups or venerate genocidal colonists or enslavers, settler-colonial naming practices can help to reproduce ongoing structures of oppression. As the name “Homesteader’s Gap” attests, even the most milquetoast settler-colonial place names can be put to work to naturalize the settler-colonial perspective on the land as a resource to own and exploit.

The DOI renaming initiative is the most ambitious renaming effort in our country’s history, and we can learn a great deal from its strengths and weaknesses. On one hand, it is clear that the federal renaming initiative has offered communities the opportunity to take some control over which histories and values are enshrined on street signs and maps. On the other hand, we can see that there are limitations to framing renaming parameters around a subjective notion of “offensive”—a moving target that changes over time, depending on whose perspective is prioritized.

Place-names are word-monuments: they signal our shared values and serve as potent symbols, impacting how we perceive, distribute, and demonstrate power. In our age of multiple overlapping and intensifying crises, we have a once in a generation opportunity to topple the word-monuments that naturalize the exploitative and extractive system that got us here.

This is not simply a matter of elevating one community’s heritage and denigrating another’s. Nor is it a matter of making the settler-colonial world less offensive.

This is a struggle between two worlds. One is based on a logic of competition and profit, and its laws and logics lie at the foundation of the social and ecological crises we face today. The other recognizes our mutual dependency–between people, plants, animals, water and land.

The place names worth fighting for point to this second world.