FEATURE

Remapping The World: The Global Context

SHARE

Place-names locate us in place, but also in relation to other places, not just across the country, but around the world. Place-names also locate us in time. Indigenous-led renaming campaigns remind us that there are other naming traditions that refer to times before and after colonial rule. They dislodge the sense of inevitability and permanence so often attributed to the colonial map, exposing colonial place-names as historical, but far from inevitable.

Across the world, colonial governments have made concerted efforts to replace Indigenous place-names in order to assert power and control over territories. From the British government’s strict and systematic implementation of the English language to name streets, cities, buildings, and schools throughout colonial India, to the State of Israel’s erasure of Arabic place-names following the Nakba of 1948, colonial place-naming practices have served to “nativize” colonial administrations and settler populations, while attempting to make Indigenous populations feel like foreigners in their own homelands. Referring to the Palestinian experience under Israeli authority, Palestinian political educator Umar al-Ghubari explains:

“In almost every place in the country they want us to feel foreign. ‘This is not your country, this is the country of the Jews’, the signs report to us. Our feeling is that we’re in a constant struggle for our consciousness. Our struggle, then, is not only against the rulers, but also against the signs.”

The centrality of place-names to everyday life has marked them as key sites for ideological work: tools for delineating who does and does not belong.

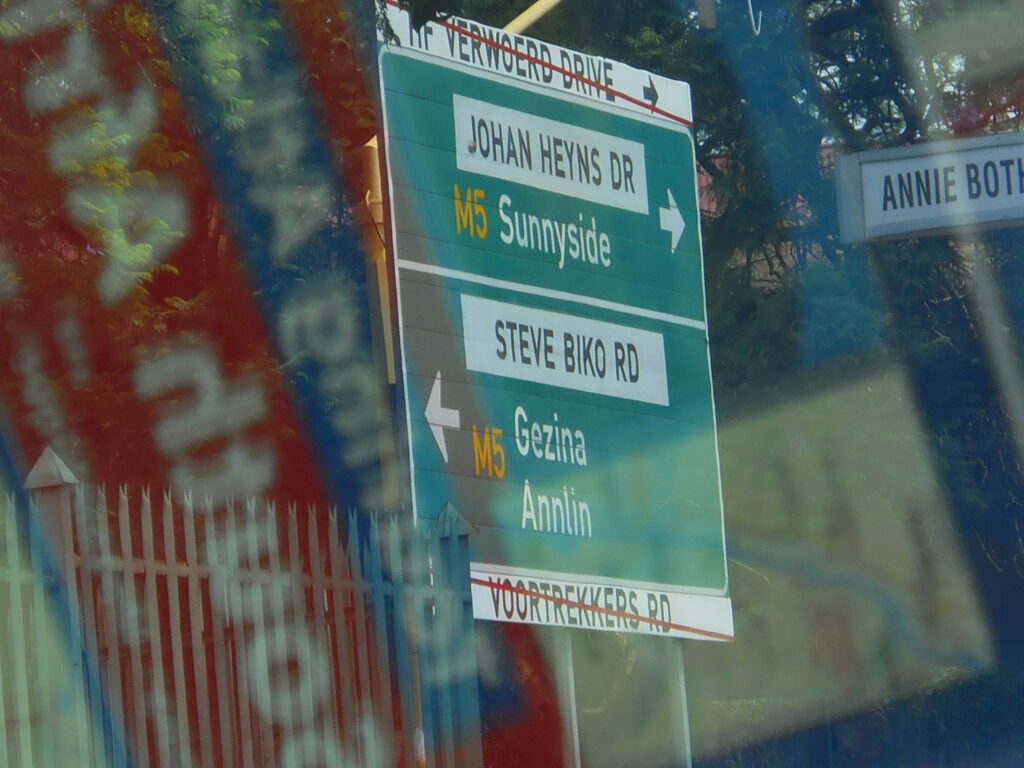

From Apartheid-era South Africa, to Palestine, to New Zealand, Indigenous populations have endured centuries of colonial oppression without giving up their deep cultural ties to their homelands, thanks to a wide array of informal tactics of resistance: from defacing official street signs, to ignoring official place-names and continuing to use the ones that preceded them, to passing on their Native languages to their children even when these languages have been outlawed, to trespassing on federal lands and across closed borders as though such enclosures are meaningless. Everyday acts of refusal have been integral to the long-term, inter-generational struggles of dispossessed peoples around the world. They have enabled dispossessed peoples to forge and maintain subaltern consciousness until the moment of decolonial reckoning.

Renaming Campaigns

Renaming campaigns have also led to significant official changes. In post-Apartheid South Africa, Durban, named after the British governor of the Cape Colony, was renamed eThekwini, its Zulu name. Pretoria, named after the first president of the South African Republic, was renamed Tshwane, which is what the Tswana people had always called the place. In New Zealand, where Te Reo Māori was declared as one of the country’s two official languages in 1987, the Māori Party has recently launched a petition to change the country’s official name to Aotearoa, its name in the Te Reo Māori language.

Renaming campaigns have not been the sole province of Indigenous populations. After the storming of the Winter Palace, the Bolsheviks in Russia moved to rename streets that referred to the Tsarist autocracy, which had enforced brutal conditions on workers and peasants throughout the Empire. During the Paris Commune of 1871, where working class Communards had seized control of Paris for two months, they renamed Place de La République as Place de la Commune, resignifying a monument to the bourgeois revolution as a monument to egalitarian emancipation. In the wake of the Egyptian revolution of 1952, which marked both the abolition of constitutional monarchy and the end of British occupation in the country, Cairo’s Ismailia Square—named after the nineteenth century monarch Ismail the Magnificent—was consecrated as Tahrir Square (translated as Liberation Square). True to its new name, Tahrir Square has since become a key site for popular protests and demonstrations, from the 1977 Bread Riots to the 2003 protests against the War in Iraq, to the 2011 Egyptian revolution.

While the naming practices of authoritarian and colonial governments serve to naturalize their dominion over the lands they control, campaigns to rename places from below can serve the opposite. They can signal tectonic shifts in power, as well as key opportunities for people to come together to expand their power, to not only refuse the coordinates set by the colonial map, but also to map the world otherwise. Popular renaming campaigns builds on deep-rooted struggles—not only the everyday, covert struggles of local peoples who refuse to give up on their cultures in the face of colonial oppression, but also the struggles of people in other places, who are mounting renaming campaigns in response to their own histories of displacement and dispossession. From the United States to South Africa, to Palestine, to Aotearoa, renaming campaigns are revising the coordinates through which we navigate space and place, testifying to a movement that is reverberating across the world.