Cartography has played a significant role in the acquisition of new territories by colonial governments—not only by putting colonial regimes of land ownership on paper, but also by providing an impetus and a cover for colonial expansion.

Before setting out on the Corps of Discovery of 1803-1806, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were trained in the tools of natural history, including cartography, geology, and botany. The Lewis and Clark Expedition was an effort to map the West, but for the US government, mapping was a means to another end. Commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson after the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, the Expedition was charged with the task of finding “the most direct and practicable water communication across this continent, for the purposes of commerce.”

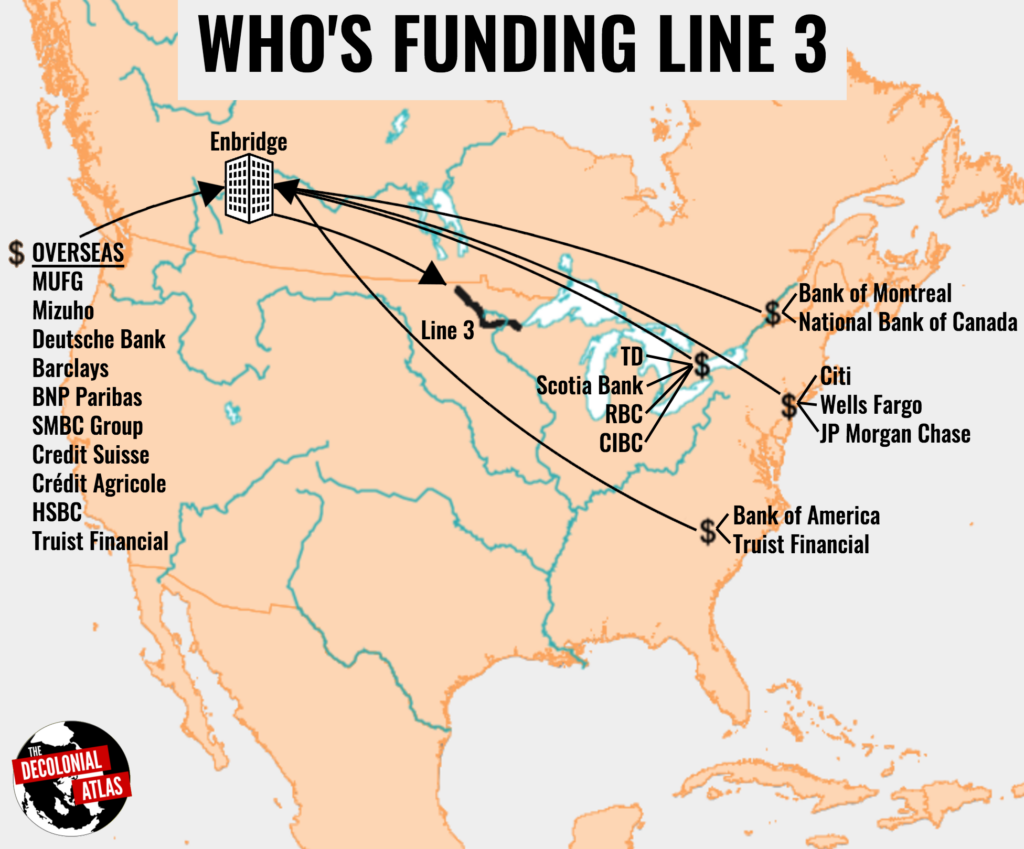

But the Expedition wasn’t simply about finding a good route to the Pacific Ocean. It was also about claiming the West as the sovereign territory of the United States, as well as gaining intelligence on Indigenous Nations and the lands they stewarded in order to strategize for their conquest. Surveys of flora, fauna, peoples, and territories were central to this project, revealing some of the ways in which the tools of surveying and the tools of surveillance have been deployed as weapons. The Corps of Discovery’s disingenuous claim to benevolent neutrality resonates with our own moment, when too often new cartographic and biodiversity studies are conducted to help make the case for building contested fossil fuel infrastructures on Indigenous lands.

Cartography has been a significant tool in the expropriation of Indigenous lands at every stage of enclosure. In the US, the establishment of the Indian Reservation System required the mapping of borders between Reservations and private lands. The General Allotment Act of 1887 required the same territories to be remapped, divided up into privately-owned allotments. At every turn, colonial maps conjoin with juridical frameworks to legally enshrine the sanctity of private property—the basic unit of capitalist economic development.

If it’s clear that maps have been central to the twin projects of colonial dispossession and capital accumulation, can they be mobilized in the other direction, not in the interest of accumulation, surveillance, and control, but collective liberation?

Jordan Engel, a cartographer and researcher at the Decolonial Atlas project, argues that they can:

“Even though Europeans were the first people to map the world, non-European peoples do not have to forfeit their right to map their lands in their own way. Mapmaking is an art, not a science, and the rigid international standardization that has been applied to it stifles individual and cultural expression.”

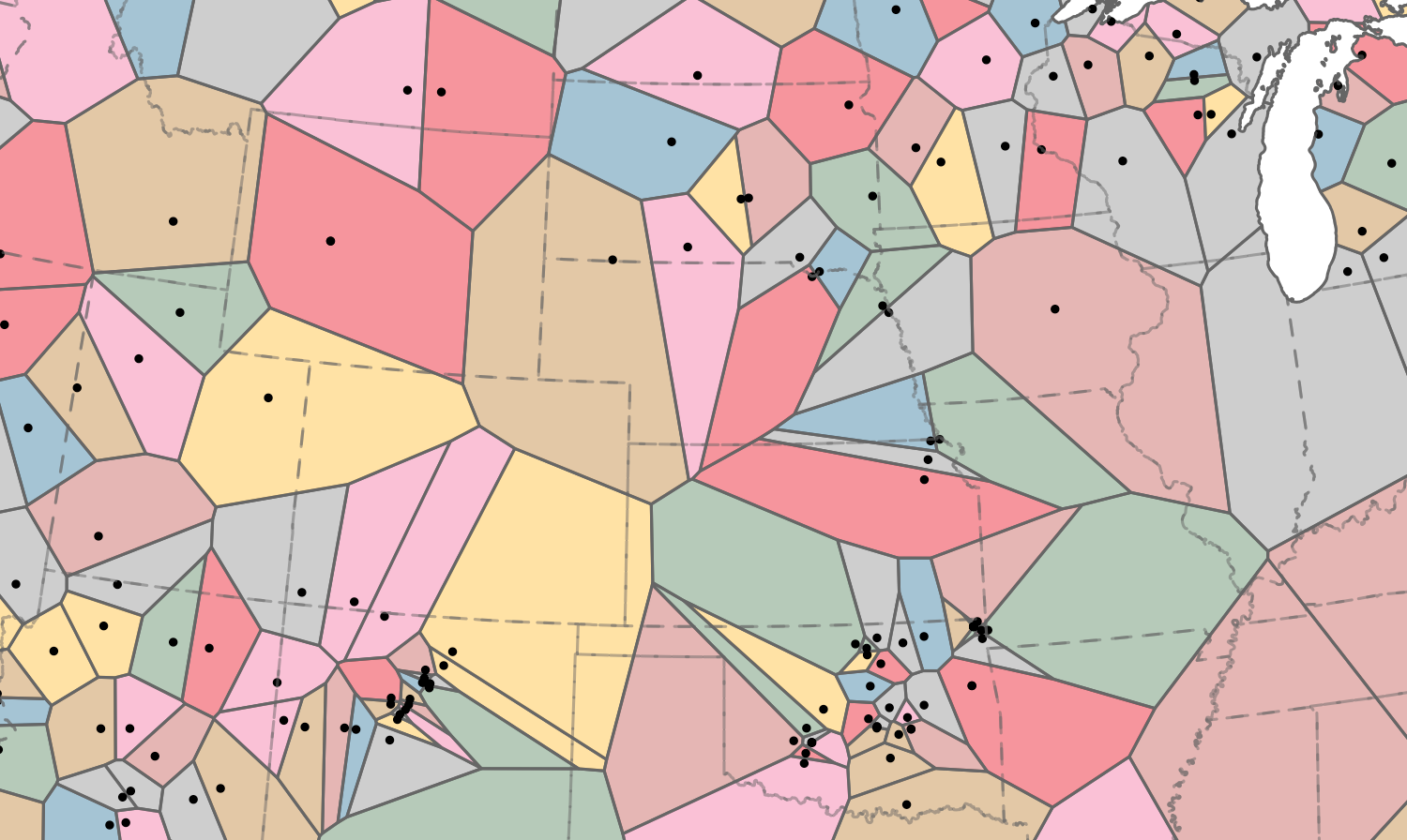

Founded in 2014, the Decolonial Atlas Project is a repository of maps that run against the grain of the colonial tradition of cartography. In an excellent introduction to decolonial mapmaking, Engel explains:

“The Decolonial Atlas is a grassroots mapping project, the purpose of which is to bring together maps that, in some way, challenge our relationships with the environment and the dominant culture. Over the course of the project, Indigenous language speakers from around the world have contributed their knowledge to produce maps from their particular cultural perspectives. The maps are usually borderless, with the exception of some that depict bioregional borders such as basin divides. There are maps oriented in every cardinal direction, depending on the traditions of that culture. To date, we have produced new maps in Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe), Gaeilge (Irish), Hinono’eitiit (Arapaho), Kanien’kéha (Mohawk), Lakȟótiyapi (Lakota), Māori (Maori), Meshkwahkihaki (Fox), Myaamia (Miami-Illinois), Nāhuatlahtōlli (Nahuatl), ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian), Runa Simi (Quechua), Tamaziɣt (Berber), Tsoyaha (Yuchi), and more. They range in scale from metropolitan regions to global.”

In its commitment to mapping for the common good, Decolonial Atlas isn’t alone. Indeed, the Atlas comes out of a long tradition of counter-mapping, which has been central to social movements and grassroots organizing for decades. Some recent examples include:

- The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, which has been developing numerous tools to document “dispossession and resistance upon gentrifying landscapes” in the Bay Area.

- Environmental Justice Atlas, which “collects stories of communities struggling for environmental justice from around the world. It aims to make these mobilizations more visible, highlight claims and testimonies and to make the case for true corporate and state accountability for the injustices inflicted through their activities.”

- Native-Land.ca, an online tool that helps people across the world to figure out whose stolen land they are on, with the goal of “creat[ing] spaces where non-Indigenous people can be invited and challenged to learn more about the lands they inhabit, the history of those lands, and how to actively be part of a better future going forward together.”

- Watch the Mediterranean Sea, “an online mapping platform to monitor the deaths and violations of migrants’ rights at the maritime borders of the EU.”

- Dual Power Map, a new tool, developed by Black Socialists of America, which maps an organizational infrastructure for dual power—grassroots institutions and organizations throughout the US that are “dedicated to building a directly democratic, ecologically sustainable, post-scarcity community and society.”

- Forensic Architecture, which uses the tools of spatial analysis (including 3D modeling and map-making) “in the service of human rights and environmental investigations and in support of communities exposed to state violence and persecution.”

One more example: at last summer’s Red Road to DC, The Natural History Museum and partners from the Lummi Nation’s House of Tears Carvers, Se’Si’Le and Native Organizers Alliance drew from the long tradition of counter-mapping, not to make a new map, but to “draw lines” between place-based struggles occurring in different places across the country. The Red Road to DC was a cross-country totem pole journey that aimed to support local communities’ efforts to protect sacred places threatened by dams, mining, and oil and gas extraction. The journey highlighted the critical importance of Tribal Nations in decisions on land, water and infrastructure projects, and demanded that the U.S. government respects the international legal standard of free, prior, and informed consent in its negotiations with Tribal Nations.

Whether developed online or on the ground, these counter-mapping initiatives point in the direction of what geographer Cindi Katz’s calls “counter-topography”: a metaphor and method for tracing “contour lines” between the localized impacts of macro-scale processes, not only to chart capitalism’s diverse and devastating impacts on communities across the world, but also to reveal common grounds between people facing these impacts in wildly different places. Counter-mapping is a means of drawing new lines of solidarity, which, in turn, contributes to the production of new conditions for struggling both in a place, and between one place and another.

In the spirit of this diverse array of counter-mapping initiatives, renaming campaigns take on the project of mapping the world according to coordinates that bend toward justice and liberation. What makes renaming campaigns distinct from the others is their specific ambition: not to chart new, alternative maps, but to transform the official maps that people across the world use to navigate space and place.