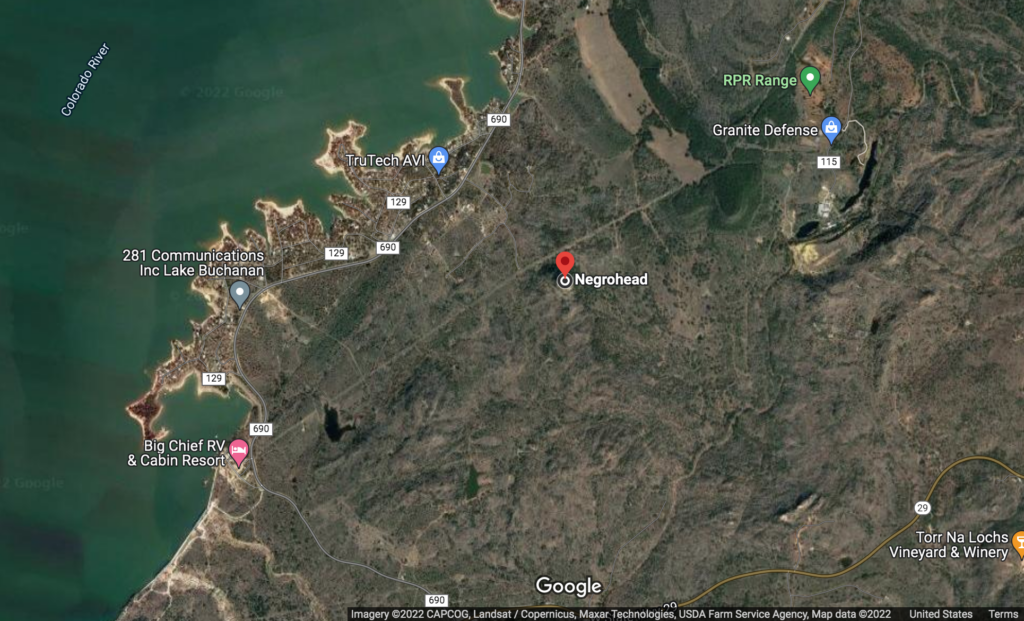

Sometimes renaming campaigns need one final push. This was recently the case in Texas, where nearly 30 years after Texas lawmakers voted to change the names of 19 sites that included the word “Negro” in their names, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names finally signed off in the Summer of 2021.

As Daniel Victor and Jesus Jiménez report in the New York Times:

“It was a long time coming,” said Rodney Ellis, a Harris County commissioner, who nearly 30 years ago sponsored a Texas law demanding renaming. “Just as we say ‘Black lives matter,’ names matter. They matter a lot.”

The United States has a long history of towns and geographical features with racist names, and recent decades are dotted with efforts to change them. Many have been renamed, but other efforts have been met with resistance, often by locals who take pride in their history and see no reason to change.

See, as one example, White Settlement, Texas.

“People chose to give these offensive names to roads and rivers and creeks because they wanted to make a statement, a statement that would go beyond their voice, beyond that generation,” Mr. Ellis said. “If it’s a statement that is not something we want people to emulate, we should recognize that.”

This approval came, not incidentally, in the wake of the George Floyd uprisings of 2020, when nearly 100 monuments to confederate generals like Robert E. Lee were toppled at sites around the country, the Confederate Flag was officially retired as the state flag of Mississippi, and when an estimated 15 million to 26 million people joined together to denounce the racist structures of dominance that continue to make Black people in the United States vulnerable to premature death.

In the face of the overwhelming injustice experienced by Black people in the United States—so frequently in the name of the Justice System—it is understandable that some activists and commentators are impatient with the symbolic struggles of the past several years. When the Mayor of the District of Columbia, Muriel Bowser announced the renaming of a section of the street outside the White House as Black Lives Matter Plaza in June 2020, many activists were asking the same question:

What material transformations arise from a name change?

Debates over the merits of struggles over symbols loom large in the field of social justice activism, organizing, and theory. There are certainly no guarantees that meaningful structural or material changes will arise from successful monument struggles or renaming campaigns. But if the monument removals of the past two years have taught us anything, it is that symbolic struggles shape popular consciousness, revealing the collective capacity of the people to set the coordinates through which we navigate space.

Monument removals and renaming campaigns are not only about history, but also about the present. They are part of a broad struggle to determine the symbols that orient people to place. As we saw so clearly during the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, white supremacist symbols like Confederate flags do not only function as reminders of an oppressive past; they have present use value, which the far right is mobilizing to great effect.

Taking a bird’s eye view of the monument removals, counter-monuments, renaming campaigns and successful place name changes taking place across the country, we can also see the common ground shared by struggles that are too often understood as discrete. From Texas to Yellowstone and beyond, renaming campaigns arise from specific struggles for racial justice and Indigenous sovereignty, but they conjoin in one struggle to remap the world.