“For us, place-names are very sacred and spiritual. By returning our traditional place-names to our ancestral lands, the spirits of the areas will again hear their true names and will bring healing to the land and people.”

Mr. Lee Juan Tyler, Shoshone-Bannock Tribes Council Member

While the federal government recently announced plans to replace 660 place-names with the derogatory term “sq**w”, a new study published today in the journal People and Nature shows that derogatory place-names are only the tip of the iceberg. Violence in place-names takes many forms, from valorizing racist colonizers and Confederate leaders, to commemorating atrocities, to erasing Indigenous cultures.

Titled “Words are Monuments”, the study presents findings from a quantitative analysis of National Park place-names conducted by a team of six researchers—five ecologists and one specialist in ethnic studies.

The researchers explore “the degree to which place-names perpetuate settler colonial myths, including white supremacy, by looking at the pervasiveness of and spatial patterns in place-names and their meanings.” Deploying the tools of data analysis and statistics to analyze 2,200 place-names at a sample of 16 National Parks, they asked three core questions:

- Who and what do place names in US national parks commemorate?

- Do US settler colonial and racial processes show up in spatial patterns in US national park place names? If so, how?

- To what extent do place names in US national parks perpetuate settler colonial mythologies, including white supremacy?

Indigenous communities have been raising the problem of racist, derogatory, and offensive National Park place-names for decades. The Blackfeet Nation passed a resolution calling for the return of all traditional Blackfeet names to the mountains of Glacier National Park. The Puyallup Tribe has called for the renaming of Mount Rainier. And the Great Plains Tribal Chairman’s Association has petitioned for Yellowstone’s Mount Doane to be renamed First Peoples Mountain, in honor of the tribes who have stewarded these lands for millennia, and whose cultural and spiritual place-based practices continue to this day. This new audit supports these and other renaming campaigns, offering a birds-eye view on the parks system.

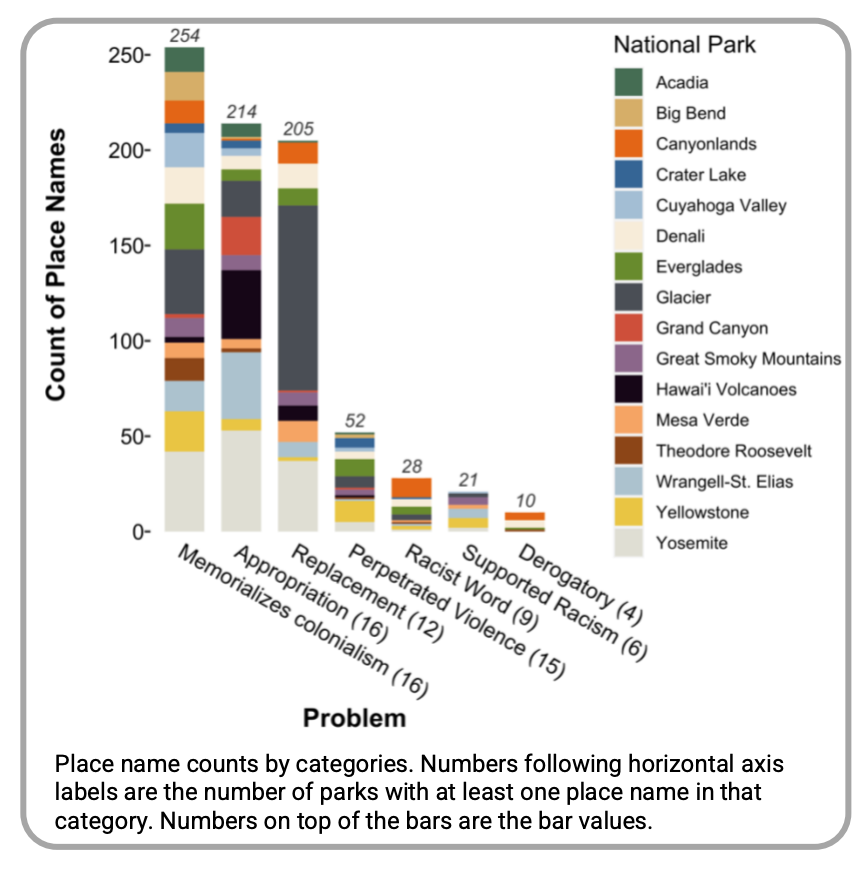

In the 16 parks examined, the study’s authors found:

- 10 place names using racial slurs, including four instances of “sq**w” (in Canyonlands and Theodore Roosevelt)

- 21 that commemorate an individual who supported racist ideas, e.g., Hayden Valley (Yellowstone).

- 52 named for a person who directly or used their power to perpetrate physical, racial violence (often anti-Indigenous genocide), including Mt. Doane (Yellowstone) and Harney River (Everglades).

- 28 place names perpetuating racist ideas

- 205 settler colonizer place names replacing a known traditional Indigenous place name, i.e., erasure of America’s cultural diversity, perpetuation of the uninhabited wilderness myth, and a whitewashing of history. Less than 5% of names bear traditional Indigenous place names.

- Only 4 place names commemorating Black people.

This data exposes “the system-wide scale at which place names reflect settler colonialism and white supremacy in U.S. national parks.” In revealing the breadth of the problem, the study suggests that a larger reckoning over word-monuments on U.S. federal lands can contribute to broader efforts to redress colonial harms and acknowledge the cultural and political sovereignty of displaced Indigenous nations, from the reinstatement of treaty rights, to the co-governance of parklands, and the rematriation of sacred places.