Mountains as Monuments

Mountains have been significant fronts in recent struggles for Indigenous sovereignty and stewardship of ancestral lands. Take the sacred peak of Mauna Kea, which Native Hawaiians have been working to protect against the proposed construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope, or Hesapa (the sacred Black Hills), which is the cornerstone of the powerful Lakota-led #LANDBACK campaign.

Last week, after a decades-long Indigenous-led campaign, Mount Doane in Yellowstone National Park has officially been renamed First People’s Mountain. This is a victory worth celebrating.

Installing Fortress Conservation

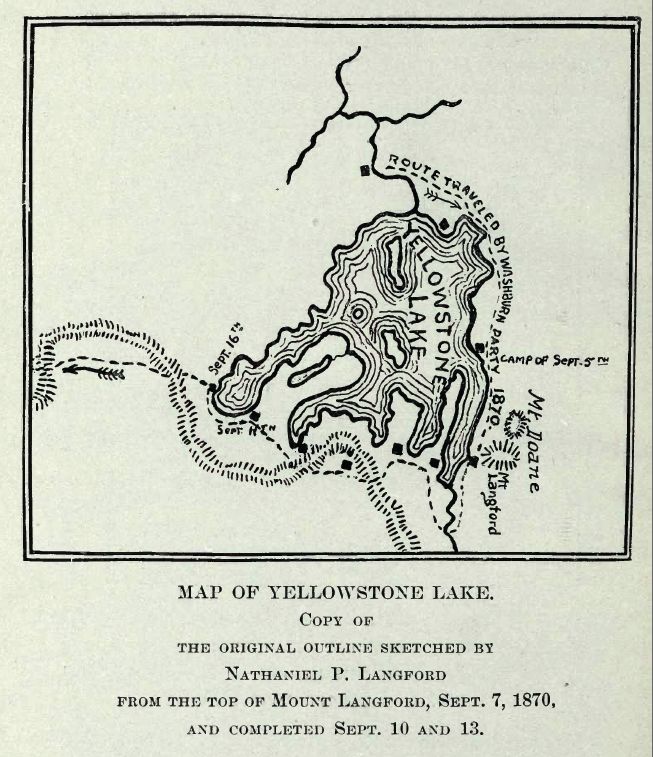

Mount Doane was named by the Hayden Geological Survey in 1871 to commemorate the life and work of Gustavus Doane. Only one year earlier, Doane played a key role in the Marias Massacre, where at least 173 Blackfeet men, women, and children were slaughtered by the US Army. This event forced the Piegan Blackfeet Tribe (along with bands of the Kiowa, Blackfeet, Cayuse, Coeur d’Alene, Shoshone, and Nez Perce) to flee their ancestral homelands, making way for the protected wilderness zone that would eventually go by the name Yellowstone.

Yellowstone was an early experiment in what some call fortress conservation. Fortress conservation involves drawing boundaries between a designated wilderness area and its outside, expelling Indigenous Peoples and keeping them out, and eradicating predator species, which are perceived as threats to ecological balance. It is grounded in the assumption that ecosystems are best preserved by policing the borders around them.

For 150 years, Mount Doane stood as a monument to the victory of the US government to seize the area known as Yellowstone, as well as to the model of fortress conservation that this seizure made possible. Consecrating the mountain as Mount Doane was a symbolic gesture, part of an ideological project meant to naturalize settler claims over the land, to invisiblize the region’s traditional stewards, and to reinforce the imperialist conviction that bloodshed, military intervention, and border security are the justifiable costs of protecting the nation’s people and precious resources (from its energy reserves to its National Parks).

Breaking Down the Fortress

The National Park Service continues to use the rhetoric of fortress conservation, describing the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem as “one of the last and largest nearly intact natural ecosystems on the planet,” but the fortress is crumbling around it. As the disastrous impacts of anthropogenic climate change have begun to take their toll around the world, ecologists have come to the assessment that fortress conservation is an ineffective approach to land management, based on the fiction that entire ecosystems can be excised from the world at large, as if ecosystems were animals in a zoo.

They are not. Climatologists have spent decades explaining how carbon released into the atmosphere in the Alberta Tar Sands is contributing to melting glaciers in the Arctic, rising sea levels in South Asia, and heat waves and extreme wildfires around the world. Just this week, Yellowstone has been forced to close due to unprecedented flooding—one of at least 6 natural disasters to hit the US this week. The NPS is now working to rebuild roads and paths across Yellowstone, sections of which are “completely gone” as a result of this week’s flood.

As the edifice of fortress conservation is literally giving way, the renaming of Mount Doane as First People’s Mountain takes on a powerful meaning. The name change suggests the transformation of a monument to colonial violence into a monument to Indigenous resurgence. As a monument to societies whose sacred relation to the land was irreconcilable with the mechanistic principles of fortress conservation, First People’s Mountain is also a reminder that what is sacred can be desecrated but not destroyed. There is a world beneath the colonial enclosure, but it needs to be seen and organized around.

First People’s Mountain is a monument, but it is also an invitation. It invites us to commemorate the Indigenous Nations whose lands Yellowstone has occupied for 150 years, but also to follow the trail of unbounded life that runs through the mountain and across the world—a spirit that fortress conservation could never manage, contain, or expel. It calls on us to reckon not just with the history of the parks system, but also with the system of colonial relations it came out of, and to affirm that fortress conservation (whether in the form of western conservation, mass incarceration, or border imperialism) is incommensurate with life.

When we take up this invitation, we can see First People’s Mountain as part of our monumental infrastructure—as a sign that the borders of the fortress are breaking down everywhere around us, and as a symbol of our collective struggle to break them down in ways that make life possible for generations to come.